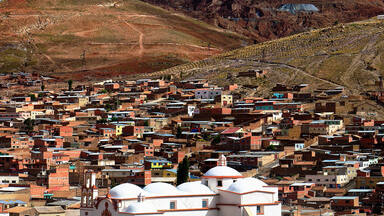

City of Potosí

City of Potosí

In the 16th century, this area was regarded as the world’s largest industrial complex. The extraction of silver ore relied on a series of hydraulic mills. The site consists of the industrial monuments of the Cerro Rico, where water is provided by an intricate system of aqueducts and artificial lakes; the colonial town with the Casa de la Moneda; the Church of San Lorenzo; several patrician houses; and the barrios mitayos, the areas where the workers lived.

Description is available under license CC-BY-SA IGO 3.0

Ville de Potosí

L’endroit était considéré au XVIe siècle comme le plus grand complexe industriel du monde. L’extraction du minerai d’argent était assurée par une série de moulins à eau. L’ensemble actuel comprend les monuments industriels du Cerro Rico, où l’eau est amenée par un système compliqué d’aqueducs et de lacs artificiels, la ville coloniale avec la Casa de la Moneda, l’église de San Lorenzo, des demeures nobles et les « barrios mitayos » qui étaient les quartiers ouvriers.

Description is available under license CC-BY-SA IGO 3.0

مدينة بوتوسي

كان هذا الموقع يُعتبر في القرن السادس عشر أكبر تجمّع صناعي في العالم حيث كان يستخرج معدن الفضة بواسطة سلسلة من الطواحين المائية. أمّا التجمّع الحالي، فيضم النصب الصناعية في سيرو ريكو حيث تُجرّ المياه بواسطة نظام معقّد من القنوات المائية والبحيرات الإصطناعية، وكذلك مدينة كازا دي لا مونيدا الاستعمارية، وكنيسة سان لورنزو، والمنازل الفخمة وأحياء العمّال، المسمّاة بالإسبانية "باريوس ميتايوس".

source: UNESCO/CPE

Description is available under license CC-BY-SA IGO 3.0

波托西城

在16世纪,波托西城被认为是世界上最大的工业复合体。银矿提炼的需要使得这里出现了一系列的水利矿场。遗址包括塞雷里科(Cerro Rico)工业建筑,复杂的引水渠和人造湖系统为该地提供水源;这座殖民城拥有卡萨德拉莫内达集镇(the Casa de la Moneda)、圣洛伦佐教堂(the Church of San Lorenzo)、一些贵族住宅区和工人居住区(barrios mitayos)。

source: UNESCO/CPE

Description is available under license CC-BY-SA IGO 3.0

Горнозаводской город Потоси

В XVI в. этот регион считался самым большим в мире промышленным комплексом. Извлечение серебряной руды осуществлялось группой фабрик, работавших с использованием гидравлической энергии. Объект состоит из индустриальных памятников Серро-Рико, куда доступ воды обеспечивался сложной системой акведуков и водохранилищ; колониального города с Монетным двором; церковью Сан-Лоренцо; несколькими домами аристократов и «барриос митайос» – территориями, где жили рабочие.

source: UNESCO/CPE

Description is available under license CC-BY-SA IGO 3.0

Ciudad de Potosí

En el siglo XVI, se consideraba que Potosí era el mayor complejo industrial del mundo. La extracción de su mineral de plata se efectuaba mediante molinos hidrí¡ulicos. El sitio actual comprende no sólo las antiguas instalaciones industriales del Cerro Rico, a las que llega el agua por medio de un sistema intrincado de acueductos y lagos artificiales, sino también el barrio colonial con la Casa de la Moneda, la iglesia de San Lorenzo, varias mansiones nobles y los barrios de los mitayos que trabajaban en las minas.

source: UNESCO/CPE

Description is available under license CC-BY-SA IGO 3.0

ポトシ市街

ボリビア高地、標高3500mの荒涼としたアンデス山中の都市。1545年に大銀鉱が発見された後、スペイン人の町ができ、18世紀前半頃まで銀山の富によって多くの建築が行われてきた。その多くはメスティソ様式の特徴を強く示し、サン・ロレッソ教会などの多くの聖堂、市長の家、オタビ侯爵邸(現国立銀行)、エレーラ邸(現大学)など多数が現存している。世界遺産には72あった銀の精錬所などの産業遺産も残されている。source: NFUAJ

Potosí (stad)

In de 16e eeuw gold het gebied rondom Potosí als 's werelds grootste industriële complex. Daarvoor was Potosí een klein gehucht in de ijzige eenzaamheid van de Andes. Het dankt zijn welvaart aan de ontdekking van zilver tussen 1542 en 1545 in de Cerro de Potosí, de berg ten zuiden van de stad. De zilverertswinning vond plaats met behulp van hydraulische molens. Het gebied bestaat uit het industriële Cerro Rico – met een watersysteem van aquaducten en kunstmatige meren, de koloniale stad met het Casa de la Moneda, de kerk van San Lorenzo, verschillende patriciërshuizen en de barrios mitayos, gebieden waar de arbeiders woonden.

Source: unesco.nl

Outstanding Universal Value

Brief synthesis

Potosí is the example par excellence of a major silvers mine of the modern era, reputed to be the world’s largest industrial complex in the 16th century. A small pre-Hispanic-period hamlet perched at an altitude of 4,000 m in the icy solitude of the Bolivian Andes, Potosí became an “Imperial City” following the visit of Francisco de Toledo in 1572. It and its region prospered enormously following the discovery of the New World’s biggest silver lodes in the Cerro de Potosí south of the city. The major colonial-era supplier of silver for Spain, Potosí was directly and tangibly associated with the massive import of precious metals to Seville, which precipitated a flood of Spanish currency and resulted in globally significant economic changes in the 16th century. The whole industrial production chain from the mines to the Royal Mint has been conserved, and the underlying social context is equally well illustrated, with quarters for the Spanish colonists and for the forced labourers separated from each other by an artificial river. Potosí also exerted a lasting influence on the development of architecture and monumental arts in the central region of the Andes by spreading the forms of a baroque style that incorporated native Indian influences.

By the 17th century there were 160,000 colonists living in Potosí along with 13,500 Indians who were forced to work in the mines under the system of mita (mandatory labour). The Cerro de Potosí reached full production capacity after 1580, when a Peruvian-developed mining technique known as patio, in which the extraction of silver ore relied on a series of hydraulic mills and mercury amalgamation, was implemented. The industrial infrastructure comprised 22 lagunas or reservoirs, from which a forced flow of water produced the hydraulic power to activate 140 ingenios or mills to grind silver ore. The ground ore was amalgamated with mercury in refractory earthen kilns, moulded into bars, stamped with the mark of the Royal Mint and taken to Spain.

The city and region retain evocative evidence of this activity, which slowed significantly after 1800 but still continues. This includes mines, notably the Royal mine complex, the biggest and best-conserved of the some 5,000 operations that riddled the high plateau and its valleys, dams that controlled the water that activated the ore-grinding mills, aqueducts, milling centres and kilns. Other evidence includes the superb monuments of the colonial city, among them 22 parish or monastic churches, the imposing Compañía de Jesús (Society of Jesus) tower and the Cathedral. The Casa de la Moneda (Royal Mint), reconstructed in 1759, as well as a number of patrician homes, whose luxury contrasted with the bareness of the rancherias of the native quarter, also remain. Many of these edifices are in an “Andean Baroque” style that incorporates Indian influences. This inventive architecture, which reflects the rich social and religious life of the time, had a lasting influence on the development of architecture and monumental arts in the central region of the Andes.

Criterion (ii): The “Imperial City” of Potosí, such as it became following the visit of Francisco de Toledo in 1572, exerted lasting influence on the development of architecture and monumental arts in the central region of the Andes by spreading the forms of a baroque style incorporating Indian influences.

Criterion (iv): Potosí is the one example par excellence of a major silver mine in modern times. The industrial infrastructure comprised 22 lagunas or reservoirs, from which a forced flow of water produced the hydraulic power to activate the 140 ingenios or mills to grind silver ore. The ground ore was then amalgamated with mercury in refractory earthen kilns called huayras or guayras. It was then molded into bars and stamped with the mark of the Royal Mint. From the mine to the Royal Mint (reconstructed in 1759), the whole production chain is conserved, along with the dams, aqueducts, milling centres and kilns. The social context is equally well represented: the Spanish zone, with its monuments, and the very poor native zone are separated by an artificial river.

Criterion (vi): Potosí is directly and tangibly associated with an event of outstanding universal significance: the economic change brought about in the 16th century by the flood of Spanish currency resulting from the massive import of precious metals in Seville.

Integrity

Within the boundaries of the property are located all the elements necessary to express the Outstanding Universal Value of the City of Potosí, including the ensemble’s industrial mining and urban components such as the system of artificial lakes, the mines, the mineral processing mills, the architecture and urban form and the natural environment, all dominated by the majestic presence of Cerro de Potosí. No buffer zone for the property has been delimited.

Authenticity

The City of Potosí is authentic in terms of the ensemble’s forms and designs, materials and substances, and location and setting. Still dominated by the majestic Cerro de Potosí, the “Imperial City” of Potosí’s streets, squares, civic and religious buildings, parishes and churches remain as faithful witnesses of its great splendour and tell the important history of mining in the Americas.

The degradation of Cerro de Potosí (also called Cerro Rico [Rich Mountain] or Sumaj Orcko) by continuing mining operations has long been a concern, as hundreds of years of mining have left the mountain porous and unstable. The Bolivian Mining Corporation included the preservation of the form, topography and natural environment of the mountain as one of the objectives for its future exploitation. Nevertheless, recommendations by a World Heritage Centre/ICOMOS technical mission in 2005 to improve the security and stability of the property, as well as other conditions necessary to allow for sustainable mining activities, were not addressed and portions of the summit of the mountain have collapsed. The authenticity of the property is thus threatened, and urgent and appropriate action must be taken to protect human lives, to improve working conditions and to prevent further deterioration of this vulnerable component of the property.

Protection and management requirements

The City of Potosí is protected under the Constitución Política del Estado (Political Constitution of the State), Art. 191; Ley del Monumento Nacional (National Monument Act), 8/5/1927; Normas Complementarias sobre patrimonio Artístico, Histórico, Arqueológico y Monumenta (Complementary Standards on Artistic, Historical, Archaeological and Monumental Heritage), Decreto Supremo (D.S.) No. 05918 of 6/11/1961; Créase la Comisión Nacional de Restauración y Puesta en Valor de Potosí (Establishment of the National Commission for the Restoration and Revitalization of Potosí), D.S. No. 15616 of 11/7/1978; Normas sobre defensa del Tesoro Cultural de la Nación (Standards for the Protection of the National Cultural Treasure), Decreto Ley (D.L.) No. 15900 of 19/10/1978; and Act No. 600 of 23/2/1984 to finance the implementation of the designation of the City of Potosí as a “Monumental City of America” by the General Assembly of the Organization of American States in 1979. In addition the Plan de Rehabilitación de las Áreas Históricas de Potosí - PRAHP (Rehabilitation Plan of the Historic Areas of Potosí), its Regulations and several studies also encompass the protection of the property. There is no participatory conservation management plan for the property.

Restoration work is realized by international support from UNESCO, the Organization of American States and the governments of Spain and the Federal Republic of Germany. The Ministry of Culture of the Plurinational State of Bolivia is in charge of conservation and preservation work. The Proyecto de la calle Quijarro (Quijarro Street Project) was developed in 1981 to encourage rehabilitation of homes in the historic downtown areas; basic services are provided in collaboration with the Municipality - of Potosí. However, it should be noted that there is a strong economic downturn in the region. It is expected that cultural tourism will help provide social, economic and educational support.

Sustaining the Outstanding Universal Value of the property over time will require fully implementing the emergency and other measures identified by the 2011 technical mission; finalizing and implementing an approved Strategic Emergency Plan, including rationalization and planning of industrial exploitation in the area; developing and implementing approved measures to ensure the structural stability of the top of the mountain; modifying Article 6 of Supreme Decree 27787 to halt all exploration, extraction and any other interventions under and above ground between altitudes 4,400 m and 4,700 m; completing an analysis and modelling based on recent geophysical studies to further identify the anomalies affecting the mountain; putting in place a monitoring system; finalizing and submitting a participatory Management Plan for the property; and delimiting a buffer zone for the property.