Testing the role of digital technologies in recording values of human settlements in Asia and the Pacific

For four years, a team at the University of Queensland tested new and old technologies, such as photogrammetry, laser scanning and community mapping, to record the interaction between tangible and intangible layers of traditional human settlements in China and India.

About the project

Between 2017 and 2020, an international research project sought to test different methodologies and possibilities of digital technologies to record traditional and vernacular settlements in Asia. The project team was composed of Dr Kelly Greenop, senior lecturer and researcher, and then PhD candidates, now graduates, Dr Kali Marnane and Dr Xiaoxin Zhao, from the School of Architecture, University of Queensland, Australia.

The project used new technologies, such as mobile 3D laser scanning, photogrammetry and voice recordings, joined with analogue tools such as interviews, charrettes and hand drawings to record the relationship between the built environment and its inhabitants. The viability of the different tools was tested in two practical studies in Ahmadabad, India, and Lili, China. The outcomes of the project show the potential of digital technologies to record tangible and intangible attributes of urban landscapes, leading to their valorisation and enhancement, and increasing awareness. At the same time, the experience shows that digital tools are also a good way to increase public interest in heritage, especially concerning the youth.

“A lot of decisions are being made because the physical landscape is valued over the social or cultural landscape. And what we found was that they are completely interlinked, and you cannot separate them. One is not more important than the other and both need to be considered in our role as architects or researchers.”

Case Study 1: Lili, China

Lili is a traditional canal town located in eastern China. The town has been subject to some regeneration proposals for its development as a tourist destination. However, at the time of the study, its economy was struggling, and residents were leaving for bigger cities. At the same time, the authenticity of the historic town was still there, thanks to the memories and heritage of mostly elderly residents. In this context, the team identified the potential to record the traditional settlement and its values and inform potential developments. This record would also be useful in the context of a local initiative to propose a nomination for Chinese canal towns for inscription on the World Heritage List.

Case Study 2: Ahmadabad, India

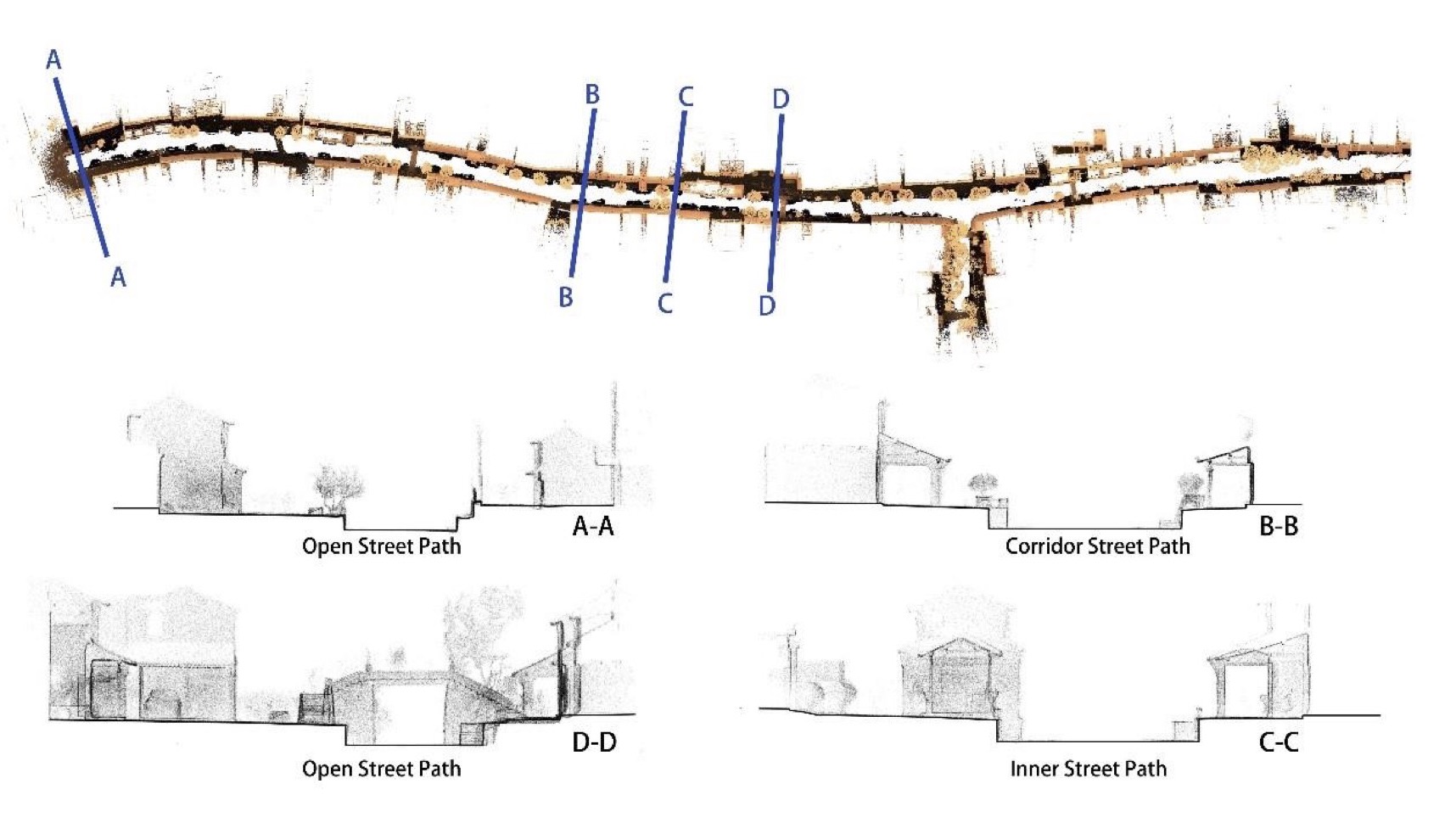

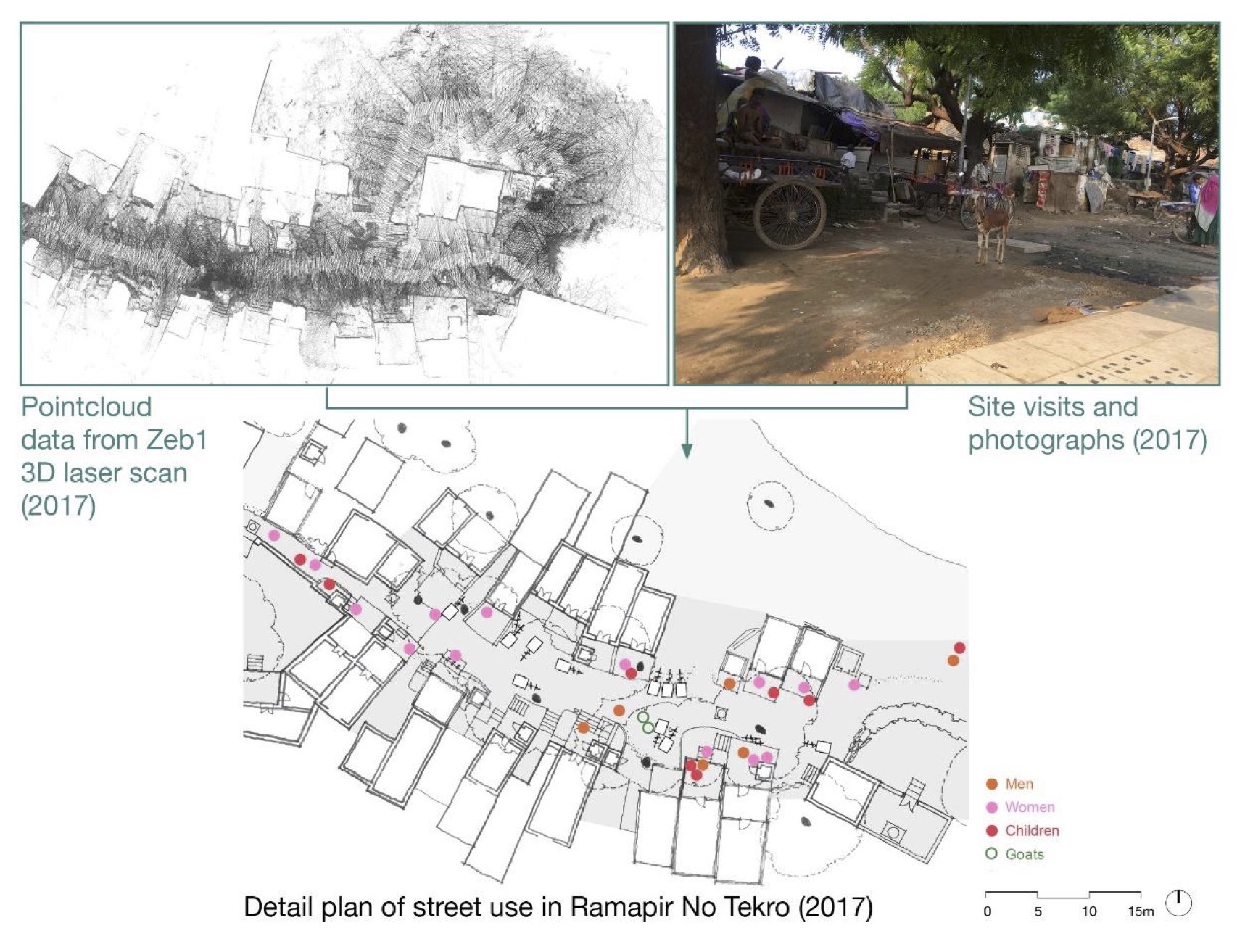

Ahmadabad is one of India’s largest metropolises in the western region of Gujarat. Its historic centre, the Historic City of Ahmadabad, was inscribed on the World Heritage List in 2017. However, the case study did not focus on the Historic City, but on the informal settlement of Ramapir No Tekro, five kilometres to the northwest of the World Heritage property. The case study in Rampair No Tekro sought to challenge existing perceptions about informal settlements, approaching them with a cultural heritage perspective. In fact, the results showed a close relationship between the attributes of the Historic City and the informal settlement. For instance, many of the spatial patterns in the informal settlement were similar to those found in the World Heritage site, especially regarding the social structure of the neighbourhoods, the arrangement of shared spaces, and the outdoor living spaces or thresholds – albeit with more humble materials and smaller sizes.

Context and drivers

Vernacular architecture is difficult and laborious to record using traditional methods, such as architectural surveys, due to its irregular planning and non-orthogonal layouts. Mobile 3D laser scanning technology has the potential to be particularly helpful and accurate in these complex environments. In fact, 3D laser scanning is today widely used to capture the built environment, especially static elements such as building facades and monuments.

However, stationary scanners are not a viable solution for densely inhabited living settlements: on the one hand, the complex geometry and continuous activity make the task technically difficult. On the other hand, because the stationary scanners record very detailed and accurate data, the size of the data can become hard to manage in large sites, such as settlements or landscapes.

With the goal of exploring the potential of mobile 3D scanning for vernacular architecture and settlements, the researchers prompted the University of Queensland to invest in mobile hand-held scanners (Zebedee and later ZebRevo), technologies originally developed to be used in mining. This tool was then available for researchers and PhD students free of charge.

Methodology

Within the wider goal of capturing the values and attributes of traditional settlements, the team developed a toolbox of mapping instruments that included both new digital tools and more traditional methods.

The first step in both cases was to build relationships with local stakeholders and engage the communities. In Ahmadabad, researcher Kali Marnane collaborated with NGOs Manav Sadhna and The Anganwadi Project, which run local community centres and preschools. In the case of Lili, researcher Xiaoxin Zhao got in contact with stakeholders such as the staff of the local museum, the local administration and the UNESCO Club.

Secondly, interviews were carried out with community members and local stakeholders. In the case of Ahmadabad, where the project was developed in collaboration with an educational NGO, the interviews focused on women and children and often took place in residents’ homes or public spaces around community centres and schools, using a voice recorder. In Lili, community mapping workshops were carried out, where residents were asked to identify on a printed map the places with important meanings and memories by using colourful stickers.

In parallel, the researchers took on the recording of the sites through a variety of means, including hand-drawings, sketches, photographs, audio recordings and 3D laser scanning. In particular, the technology used includes the hand-held Zebedee laser scanner, a portable device which allowed the researchers to capture the settlements in a relatively short time. In Lili, photogrammetry was used to capture the full three-dimensional reality: areas not accessible with the laser scanner, such as the roofs, were documented with a drone video, from which photographs were extracted. The point clouds resulting from the laser scanning and photogrammetry were then joined using OpenSource software CloudCompare.

The total recording process took approximately two months in Lili, and four months in Ahmadabad. The thorough documentation of the sites using interviews, photographs and sketches allowed the team to interpret the data off-site. A significant level of interpretation was needed – the representation of moveable elements, such as cloth-hanging lines, was not obvious in the point clouds.

Financing

To fund the research project, the team relied on a variety of funding sources. On the one hand, both PhD candidates benefitted from scholarship funding provided by the university. They were able to borrow expensive equipment from universities, such as the laser scanner from the University of Queensland and the drone from the University of Nanjing. This lowered the operational costs significantly, with the price of a drone around 3,000 AUD (approx. 1900€ as of February 2023), and a hand-held laser scanner around 40,000 AUD (26,000€). Using the hand-held laser scanner was also a cost-effective choice in comparison with a static one, both in times of purchase cost and time required for the scanning. At the same time, the project was supported by the local NGO Manav Sadhna for accommodation and knowledge finding, as well as The University of Queensland, which bore the costs of data-processing.

Challenges

Because of its experimental nature, the project had to address many technical challenges linked to the use of developing technology – for instance, concerning file sizes, storage, and batteries. These challenges were addressed, on the one hand, by the fast development of technology, and, on the other hand, by connecting with the large online community of support that exists for digital technologies. At the same time, scanned data was often difficult to interpret, especially for those who had not been onsite, making the first step of observation and community engagement essential.

Consulting and engaging with local communities proved to involve a significant amount of time and effort. In order to gain the trust of the community and local authorities, researchers worked on establishing clear communications concerning the project goals and methods. At the same time, the novelty of the technology helped to engage curious residents in the project. It is also worth noting that in many cases, community participants might need to be economically reimbursed for their participation.

A present and future challenge, which remains unresolved, is ensuring the liveability of these digital records. The researchers have identified a need to develop a standardised methodology and common policy for digital data, such as agreed file types, metadata categories and archiving.

According to the research team, the main project outcomes relate to the definition of a toolbox for the HUL-based recording of urban landscapes, with different tools which might be useful in different contexts. In the specific cases of Ahmadabad and Lili, records of heritage values and attributes were created, including heritage values to be preserved in future development, such as the relationship between the community, their way of life and the physical environment; and the relationship between physical spaces and intangible heritage practices, such as barbershop singing in Lili. Accurate plans of the current state of the built environment were also drawn up.

At the same time, the project has raised awareness about the heritage values of traditional settlements, both historic towns and informal settlements, and their tangible and intangible values and attributes. In order to promote international exchange on the heritage value of traditional settlements, the results of the study were published online through academic papers, as well as the two respective PhD thesis

Sources:

- Contributions by Dr Xiaoxin Zhao, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, School of Architecture and Urban Planning, Nanjing University (China); Dr Kali Marnane, Associate Lecturer and Postdoctoral Research Fellow, School of Architecture, The University of Queensland (Australia); Dr Kelly Greenop, Senior Lecturer in Architecture, School of Architecture, The University of Queensland (Australia), 2022

- The role of digital technologies in recording values of human settlements: testing a practical Historic Urban Landscape approach in China and India, Xiaoxin Zhao, Kali Marnane, Kelly Greenop, 2021, Digital Creativity 32(2):1-22.

Contribution towards global goals

How does this case study contribute to the global commitments of sustainable development, and heritage conservation?

Contribution towards Sustainable Development

The initiative aims to contribute towards Sustainable Development by addressing the following Sustainable Development Goals:

Goal 8. Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all.

-

Target 8.9: the initiative aims to support sustainable tourism that creates jobs and promotes local culture and products by raising awareness about the value of local historic practices and traditional businesses.

Goal 10. Reduce inequality within and among countries.

-

Target 10.2: the initiative aims to empower and promote social and political inclusion by developing participatory and inclusive methodologies for urban conservation and management.

Goal 11. Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable.

-

Target 11.2: the initiative aims to enhance inclusive and sustainable urbanization by learning from and documenting traditional living environments.

-

Target 11.3: the initiative aims to contribute to the protection and safeguarding of the world’s cultural and natural heritage by recognising the heritage values of traditional built environments and developing a people-centred methodology for mapping heritage values in human settlements.

Goal 17. Strengthen the means of implementation and revitalize the global partnership for sustainable development.

- Target 17.17: the initiative aims to contribute to building public and civil society partnerships, sharing resources and knowledge amongst universities and other institutions.

Contribution towards the implementation of the 2011 Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape

The project aims to contribute to the implementation of the Historic Urban Landscape approach by:

- Adopting a landscape approach for the mapping of human settlements, which includes the complex layering of tangible and intangible values and attributes, in order to identify values, understand their meaning for the communities, and present them in a comprehensive manner.

- Promoting university (Higher Education) cooperation on the Historic Urban Landscape at local and international levels.

- Documenting the state of urban areas and their evolution, to facilitate the evaluation of proposals for development, and to improve protective and managerial skills and procedures.

- Establishment of multi-stakeholder, multi-level partnerships to promote heritage conservation and sustainable development.

- Development of a community-centred approach which takes into consideration the local population and traditional customs.

Historic Urban Landscape Tools

Note: the described potential impacts of the projects are only indicative and based on submitted and available information. UNESCO does not endorse the specific initiatives nor ratifies their positive impact.

Learn more

Discover more about the case study and the stakeholders involved.

To learn more

- The role of digital technologies in recording values of human settlements: testing a practical Historic Urban Landscape approach in China and India, Xiaoxin Zhao, Kali Marnane, Kelly Greenop, 2021, Digital Creativity 32(2):1-22.

- An architecture of informality: the physical and social environment of two informal settlements in Ahmedabad, India, Kali Marnane, 2021, University of Queensland.

- Living heritage and place revitalisation: a study of place identity of Lili, a rural historic canal town in China, Xiaoxin Zhao, 2020, University of Queensland.

- Digital places: revealing the physical, social and cultural significance of settlements in China and India with digital technologies. Kali Marnane, Xiaoxin Zhao, 2019, FUTURE VISIONS.

Contact

Dr Kelly Greenop, Senior Lecturer in Architecture, School of Architecture, The University of Queensland (Australia).

Dr Kali Marnane, Associate Lecturer and Postdoctoral Research Fellow, School of Architecture, The University of Queensland (Australia).

- Profile: https://architecture.uq.edu.au/profile/704/kali-marnane

- Website: https://www.kalimarnane.com/

Dr Xiaoxin Zhao, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, School of Architecture and Urban Planning, Nanjing University (China).

Credits

© UNESCO, 2023. Project team: Jyoti Hosagrahar, Carlota Marijuán Rodríguez, Altynay Dyussekova, and Mirna Ashraf Ali with the collaboration of Dr Kelly Greenop, Dr Kali Marnane and Dr Xiaoxin Zhao.

Note: The cases shared in this platform address heritage protection practices in World Heritage sites and beyond. Items being showcased on this website do not entail any type of recognition or inclusion in the World Heritage list or any of its thematic programmes. The practices shared are not assessed in any way by the World Heritage Centre or presented here as model practices nor do they represent complete solutions to heritage management problems. The views expressed by experts and site managers are their own and do not necessarily reflect the views of the World Heritage Centre. The practices and views shared here are included as a way to provide insights and expand the dialogue on heritage conservation with a view to further urban heritage management practice in general.

Decisions / Resolutions (5)

The World Heritage Committee,

- Having examined Document WHC/21/44.COM/7B,

- Recalling Decision 41 COM 8B.17, adopted at its 41st session (Krakow, 2017),

- Welcomes the information provided by the State Party concerning the progress made with the documentation of buildings in the city and the scheduled completion of the Conservation Plan (encompassing the provisions of the Local Area Plan and Visitor Management Plan) by December 2020, and requests the State Party to prioritize the completion of these key elements of the management system and to provide updated information concerning:

- The completion of the documentation of historic buildings and structures in the city, particularly the distinctive ‘pol’ housing, planned for July 2021,

- The completion of the Conservation Plan, incorporating the Local Area Plan and Visitor Management Plan, planned for December 2020,

- The completion of Heritage Impact Assessments (HIA) for all major new constructions in the western section of property and in the buffer zone,

- The continued efforts to address issues of traffic congestion, pollution and the neglected ‘pol’ buildings in poor condition;

- Also welcomes the information provided by the State Party regarding the establishment of the Ahmadabad World Heritage City Trust, and also requests the State Party to continue its efforts to strengthen the capacities for urban heritage conservation at the municipal level;

- Notes the changes to the regulations for Ahmadabad in the Common Gujarat Development Control Regulations and the establishment of the Core Walled City Zone, and further requests that an accurate map, realized in accordance with the specifications of the Operational Guidelines, be provided the World Heritage Centre along with the text of the regulations (in English);

- Also notes that HIAs are required for all new developments and urges the State Party to ensure that development projects in the buffer zone are also subject to this requirement, and that information about any planned project that may have an impact on the Outstanding Universal Value of the property is submitted to the World Heritage Centre for review by the Advisory Bodies, in accordance with Paragraph 172 of the Operational Guidelines;

- Finally requests the State Party to submit to the World Heritage Centre, by 1 December 2022, an updated report on the state of conservation of the property and the implementation of the above, for examination by the World Heritage Committee at its 46th session.

The World Heritage Committee,

- Having examined Document WHC/18/42.COM/8B.Add,

- Adopts the Statements of Outstanding Universal Value for the following World Heritage properties inscribed at previous sessions of the World Heritage Committee:

- Denmark, Kujataa Greenland: Norse and Inuit Farming at the Edge of the Ice Cap;

- India, Archaeological Site of Nalanda Mahavihara (Nalanda University) at Nalanda, Bihar;

- India, Historic City of Ahmadabad;

- Iran (Islamic Republic of), Historic City of Yazd;

- Japan, Sacred Island of Okinoshima and Associated Sites in the Munakata Region;

- Poland, Tarnowskie Góry Lead-Silver-Zinc Mine and its Underground Water Management System;

- South Africa, ǂKhomani Cultural Landscape.

The World Heritage Committee,

- Having examined Documents WHC/17/41.COM/8B and WHC/17/41.COM/INF.8B1,

- Inscribes the Historic City of Ahmadabad, India, on the World Heritage List on the basis of criteria (ii) and (v);

- Takes note of the provisional Statement of Outstanding Universal Value:

Brief Synthesis

The entire walled city is taken into consideration in the preparation of the nomination due to its potential outstanding universal value to humanity. The old city is considered as an archaeological entity with its plotting which has largely survived over centuries. Its urban archaeology strengthens its historic significance on the basis of remains from the Pre-Sultanate and Sultanate periods. The urban structure of the historic city as represented by its discrete plots of land is also proposed to be protected, since this records its heritage in the form of the medieval town plan and its settlement patterns.

The architecture of the Sultanate period monuments exhibits a unique fusion of the multicultural character of the historic city. This heritage is of great national importance and is associated with the complementary traditions embodied in other religious buildings and the old city’s very rich domestic wooden architecture so as to illustrate the World Heritage significance of Ahmedabad. The settlement architecture of the historic city, with its distinctive pur (neighbourhoods), pol (residential main streets), and khadki (inner entrances to the pol) as the main constituents, which have been documented in detail, are similarly presented as an expression of community organizational network, since this also constitutes an integral component of its urban heritage.

The timber-based architecture of the historic city is of exceptional significance and is the most unique aspect of its heritage and demonstrates its significant contribution to cultural traditions, to arts and crafts, to the design of structures and the selection of materials, and to its links with myths and symbolism that emphasized its cultural connections with the occupants. The typology of the city’s domestic architecture, which has been systematically documented, is presented and interpreted as an important example of regional architecture with a community-specific function and a family lifestyle that forms an important part of its heritage. The presence of institutions belonging to many religions (Hinduism, Islam, Buddhism, Jainism, Christianity, etc.) makes the historic urban structure of the city an exceptional and even unique example of multicultural coexistence. This is another demonstration of a unique outstanding heritage that is acknowledged as being of primary importance in evaluating the heritage of the historic city.

Criterion (ii): The historic architecture of the city of the 15th century Sultanate period exhibited an important interchange of human values over its span of time which truly reflected the culture of the ruling migrant communities which were the important inhabitants of the city. Its settlement planning based on the respective tenets of human values and mutually accepted norms of communal living and sharing exhibited a great sense of settlement planning which is unique for the historic city. Its monumental buildings representative of the religious philosophy exemplified the best of the crafts and technology which actually saw growth of an important regional Sultanate architectural expression which is unparalleled in India. In order to establish their dominance in the region the Sultanate rulers recycled the parts and elements of local religious buildings to reassemble those into building of mosques in the city. Many new ones were also built in the manner of smaller edifices with maximum use of local craftsmen and masons allowing them the full freedom to employ their indigenous craftsmanship in a way that the resultant architecture developed a unique Sultanate idiom unknown in other part of the subcontinent where local traditions and crafts were accepted in religious buildings of Islam, even if they did not strictly follow the tenets for religious buildings in Islam. The monuments of Sultanate period thus provide a unique phase of development of architecture and technology for monumental arts during the 15th century period of history of western India.

Criterion (v): Ahmadabad city’s settlement planning in a hierarchy of living environment with street as also a community space is representative of the local wisdom and sense of strong community bondage. The house as a self-sufficient unit with its own provisions for water, sanitation and climatic control (the court yard as the focus) as a functional unit and its image and conception with religious symbolism expressed through wood carving and canonical bearings is the most ingenious example of habitat. This when adopted by the community as an acceptable agreeable form, generated an entire settlement pattern with once again community needs expressed in its public spaces at the settlement level. These in terms of a gate with community control, a religious place and a bird-feeder and a community well were constituents of the self-sufficient settlement of ‘pol’. Thus Ahmadabad’s settlement patterns of neighbouring close-packed pol provide an outstanding example of human habitation.

Integrity

Integrity is a measure of wholeness or intactness of the cultural heritage and its attributes. The city has evolved over a period of six centuries and has as mentioned earlier gone through successive periods of cyclic decay and growth and has survived the pressures and influences of various factors that affect a city in history. The successive phases have retained its historic character in spite of the changes, and the integrity is retained. By and large the city still exudes wholeness and intactness in its fabric and urbanity and has absorbed changes and growth with its traditional resilience.

Conditions of integrity in the historic city including topography, geomorphology, are still retained to a large degree, The hydrology and natural features have been subjected to changes due to progressive implementation of infrastructure by the local authorities. Its built environment, both historic and contemporary has been also subjected to the changes and growth in terms of city’s population and community aspirations. Its infrastructure above and below ground also has been successively added and or expanded as the need grew. Its open spaces and gardens, its land use patterns and spatial organization have largely remained unchanged as the footprints of earlier times have not been changed very much, perceptions and visual relationships (both internal and external); building heights and massing as well as all other elements of the urban character, fabric and structure have undergone change in most cases fitting within the existing historic limits and massing although some aberrations have occurred over a process of time.

Authenticity

The settlement architecture of Ahmedabad represented, as mentioned earlier a strong sense of character of its conception through domestic buildings. The wooden architecture so prominently preferred is unique to the city. The entire settlement form is very ‘organic’ in its function considering its climatic response for year round comforts for the inhabitants.

The construction of the fort, the three gates at the end of the Maidan-e-Shahi and the Jama Masjid, with a large maidan on its north and south, were the first acts of Sultan Ahmed Shah to establish this Islamic town. On either side of the Maidan-e-Shahi and on the periphery around the Jama Masjid, the ‘pur’ or suburbs came up in succeeding phases of development.

The material used in construction of domestic building for all communities is composite with timber and brick masonry. Timber also provided a very good climatic comfort and humane quality in its usage. It also was a great unifying effect in developing harmonious living environment with significant elemental control of sizes in its building elements offering this harmonious quality.

The house form exhibited a very strong sense of an accepted type for organising the plan with a central courtyard within the house irrespective of its overall size. The functions within were always typically organised around the court or along it depending on the size of the house. This was essentially similar in all communities.

The cultural trait was an authentic foundation on which the concept of ‘Mahajan’ (nobility-guild) where all the people irrespective of their religious beliefs joined and a culture of society developed where there was a great sense of social wellbeing and of sharing. This was also observed in other prominent communities of Islam and Hindu-Jain followers. The community bondage was the intrinsic duty of all people as a response to healthy co-existence. Markets were organized on this basis and all the merchants and traders became a part of this where individual interests were considered subsidiary to the collective ethics and morality. The culture shared thus also became an important source for encouraging exemplary enterprises in the city which helped progressively evolve a city into a formidable place with industry and trade positioning it globally as a major Centre.

Protection and management requirements

The city’s efforts at conservation and sustainable management of its cultural heritage are a response to the current scenario and a step towards preservation of its Outstanding Universal Value. The proposed Heritage Management Plan is an important tool for the purpose. The aim of the management plan is to ensure protection and enhancement of the Outstanding Universal Value of Historic City of Ahmadabad while promoting sustainable development using the Historic urban landscape approach. It aims at integrating cultural heritage conservation and sustainable urban development of historic areas as a key component of all decision making processes at the city, agglomeration and larger territorial level.

The Heritage Department, Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation, as the nodal agency for heritage management in Ahmadabad plays a leading role in the preparation of the Heritage Management Plan of the city. It has the support from all relevant administrative wings in the Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation, as well as authorities like the Ahmedabad Urban Development Authority as well as Archaeological Survey of India, Gujarat State Department of Archaeology, and National Monuments Authority.

- Recommends that the State Party give consideration to the following:

- Conduct comprehensive and accurate documentation of the historic buildings of the property, particularly the privately owned timber houses, according to accepted international standards of documentation of historic buildings for conservation and management purposes,

- Conduct a detailed assessment of the extent and impact of the new constructions and development projects on the western section of the property and its buffer zone,

- Ensure the effective implementation of the Heritage Management Plan and the finalisation, ratification and implementation of the modification and additions to the development control regulations,

- Complete and implement the Local Area-Heritage Plan as a part of the Heritage Conservation Plan, with a special focus on conservation of wooden historic houses,

- Prepare, approve and implement a visitor management plan for the property to complement the Heritage Management Plan and ensure an informed and sensitive development of tourism for the site,

- Enrich the Heritage Department at Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation with capacity building and technical capacity relevant to the challenging size and extent of responsibilities of the documentation, conservation and monitoring of the property and its buffer zone;

- Requests the State Party to submit to the World Heritage Centre, by 1 December 2019, a report on the implementation of the above-mentioned recommendations, for examination by the World Heritage Committee at its 44th session in 2020.

The World Heritage Committee,

- Having examined Document WHC/16/40.COM/5D,

- Recalling Decisions 32 COM 10, 32 COM 10A, 34 COM 5F.1, 36 COM 5D, 36 COM 5E and 38 COM 5E, adopted at its 32nd (Quebec City, 2008), 34th (Brasilia, 2010), 36th (Saint Petersburg, 2012) and 38th (Doha, 2014) sessions respectively,

- Welcomes the progress report on the implementation of the World Heritage Thematic Programmes and Initiatives, notes their important contribution towards implementation of the Global Strategy for representative World Heritage List, and thanks all States Parties, donors and other organizations for having contributed to achieving their objectives;

- Acknowledges the results attained by the Forest Programme, which has achieved its key objectives, and decides to phase it out; requesting the World Heritage Centre to continue to provide support in identifying, conservation and managing forests of Outstanding Universal Value, in view of their contribution to achieving the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals related to forests;

- Also acknowledges the contribution of the World Heritage Programme on Earthen Architecture to the state of conservation and management of earthen architecture worldwide and requests the World Heritage Centre to undertake the necessary steps for entrusting the main partner of the Programme, CRATerre, with the operational implementation of the Programme and to ensure the necessary institutional overview and guidance;

- Further acknowledges the results achieved by the World Heritage Cities Programme and calls States Parties and other stakeholders to provide human and financial resources ensuring the continuation of this Programme in view of its crucial importance for the conservation of the urban heritage inscribed on the World Heritage List, for the implementation of the Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape and its contribution to achieving the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals related to cities as well as for its contribution to the preparation of the New Urban Agenda;

- Acknowledges furthermore the results achieved of the World Heritage Marine Programme its contribution to achieving the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals related to oceans, also thanks Flanders, the Netherlands and France for their support, notes with concern the possible departure of key donors in 2017 and invites States Parties and other stakeholders to continue to provide human and financial resources to support for the implementation of the Programme;

- Notes the results achieved in the implementation of the World Heritage Sustainable Tourism Programme, expresses appreciation for the funding provided by the European Commission and further thanks Flanders, Germany, Malaysia, Norway and the Netherlands for their support in the implementation of the Programme's activities;

- Also notes the results achieved by the HEADS Programme, thanks Ethiopia, Germany, Mexico, Republic of Korea, Spain, South Africa and Turkey for their generous support and decides to phase out the Programme, also requesting the World Heritage Centre to continue to provide relevant support in identifying, conservation and managing of human-evolution related heritage of Outstanding Universal Value;

- Further notes the progress in the implementation of the Small Island Developing States Programme, its importance for a representative, credible and balanced World Heritage List, thanks furthermore Japan and the Netherlands for their support and also requests the States Parties and other stakeholders to continue to provide human and financial resources for the implementation of the Programme;

- Notes furthermore the results achieved in the framework of the Thematic Initiative “Astronomy and World Heritage", and further requests the World Heritage Centre to undertake the necessary steps for entrusting IAU with the operational implementation of the Programme and to ensure the necessary institutional guidance;

- Also takes note of the progress report on the Initiative on Heritage of Religious Interest, endorses the recommendations of the first Thematic Expert Consultation meeting, also thanks Bulgaria for its generous contribution and reiterates its invitation to States Parties and other stakeholders to continue to support this Initiative;

- Urges States Parties, international organizations and donors to contribute financially to the Thematic Programmes and Initiatives as the implementation of thematic priorities is no longer feasible without extra-budgetary funding;

- Requests furthermore the World Heritage Centre to submit an updated result-based report on Thematic Programmes and Initiatives, under Item 5A: Report of the World Heritage Centre on its activities, for examination by the World Heritage Committee at its 42nd session in 2018.

The World Heritage Committee,

- Having examined Document WHC-14/38.COM/5E,

- Recalling Decisions 32 COM 10, 32 COM 10A, 34 COM 5F.1, 36 COM 5D and 36 COM 5E, adopted at its 32nd (Quebec City, 2008), 34th (Brasilia, 2010) and 36th (Saint Petersburg, 2012) sessions respectively,

- Welcomes the progress report on the implementation of the World Heritage Thematic Programmes and Initiative and thanks all States Parties, donors and other organizations for having contributed to achieving their objectives;

- Acknowledges the results attained by the Forest Programme and expresses its regrets that no extrabudgetary funding could be secured and asks the World Heritage Centre to explore alternative options before phasing out the Programme;

- Notes the importance of the World Heritage Cities Programme and underlines the relevance of the Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape to provide a comprehensive and thorough framework for cities’ urban planning, conservation and sustainable development;

- Takes note that the follow-up of the HEADS Programme will be ensured in the framework of extra-budgetary projects, through extra-budgetary funding secured by the UNESCO Mexico Office from the Carlos Slim Foundation, and in coordination with the Category 2 Centre on Rock Art (Spain) and requests that the outcomes of the projects be reported to the World Heritage Committee;

- Also takes note of the results achieved by the Earthen Architecture Programme and the lack of extra-budgetary resources; further takes note that the programme will be pursued, provided that extra-budgetary funding can be secured, with the assistance of Advisory Bodies and external partners, and encourages stakeholders to ensure the follow-up of the Programme and continue supporting research and other activities in order to assist States Parties in identifying and protecting relevant sites;

- Notes the results achieved in the implementation of the Astronomy and World Heritage Initiative as well as the lack of extra-budgetary funding; also notes that the World Heritage Centre will continue basic coordination with its strategic partners, communicate the results achieved by the Advisory Bodies and other partners, and will provide advice to States Parties as requested; and also encourages stakeholders to ensure the follow-up of the Initiative and continue supporting research and other activities to assist States Parties in identifying and protecting relevant sites;

- Welcomes the progress made in the implementation of the World Heritage Sustainable Tourism Programme and in securing the extrabudgetary funding and encourages the States Parties to participate in the Programme with national activities;

- Acknowledges the results of the World Heritage Programme for Small Island Developing States (SIDS), which has been beneficial to all regions and continues to achieve its key objectives;

- Also requests the World Heritage Centre and the Advisory Bodies, with the support of interested States Parties, to continue efforts to implement the activities foreseen under the remaining Thematic Programmes in 2014-2015;

- Further encourages States Parties, international organizations and donors to contribute to the Thematic Programmes and Initiatives and further requests the World Heritage Centre to submit an updated result-based report on Thematic Programmes and Initiatives for examination by the World Heritage Committee at its 40th session in 2016.